What are gender stereotypes and why are they a problem?

There are many common gender stereotypical phrases:

“STEREOTYPE - A widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing.”

No doubt you’ll have heard one or more of the above at some point. They’re all pretty common, and many would argue, harmless joshing.

But dig a little deeper and what are they implying?

A person’s biological sex is fixed and results in a set of attributes and differences that are true of every person in that category, such as:

Girls aren’t physically strong

Girls are emotionally weak and vulnerable

Boys need to be strong and stoic

Boys behave badly – it’s just how they are

All of these phrases are based on stereotypical beliefs about what it means to be a boy, and what it means to be a girl. And how boys and girls should behave and interact. Such stereotypes are limiting, excluding and don’t reflect the rich variety of gender identities and identifications – for instance, these stereotypes homogenise ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ and exclude trans and non-binary young people. Perpetuating these ideas is problematic and limiting not just for young people but also for society.

Stereotypes are harmful

Stereotypes are prejudicial as they inform our opinion on an individual or a group before we have even met them. Stereotypes are not just harmful in their own right; they are also a stepping stone to further prejudice and discrimination.

Stereotypes are persistent

Once a stereotype is internalised, it is often hard to shift. Psychologists have found that we more easily remember information that confirms a stereotype, than information that contradicts them.

Stereotypes are pervasive

Stereotypes appear everywhere, from the media we consume to the products we buy, from our politicians to our friends and families. Everyone will have internalised some stereotypes, and may not realise how they affect our interactions with others.

Why do we work with nurseries, schools and colleges?

Tackling gender stereotypes in nurseries and schools is one way to challenge such stereotypes before they get established, and to counter the negative impact they have on a child’s choices and outcomes.

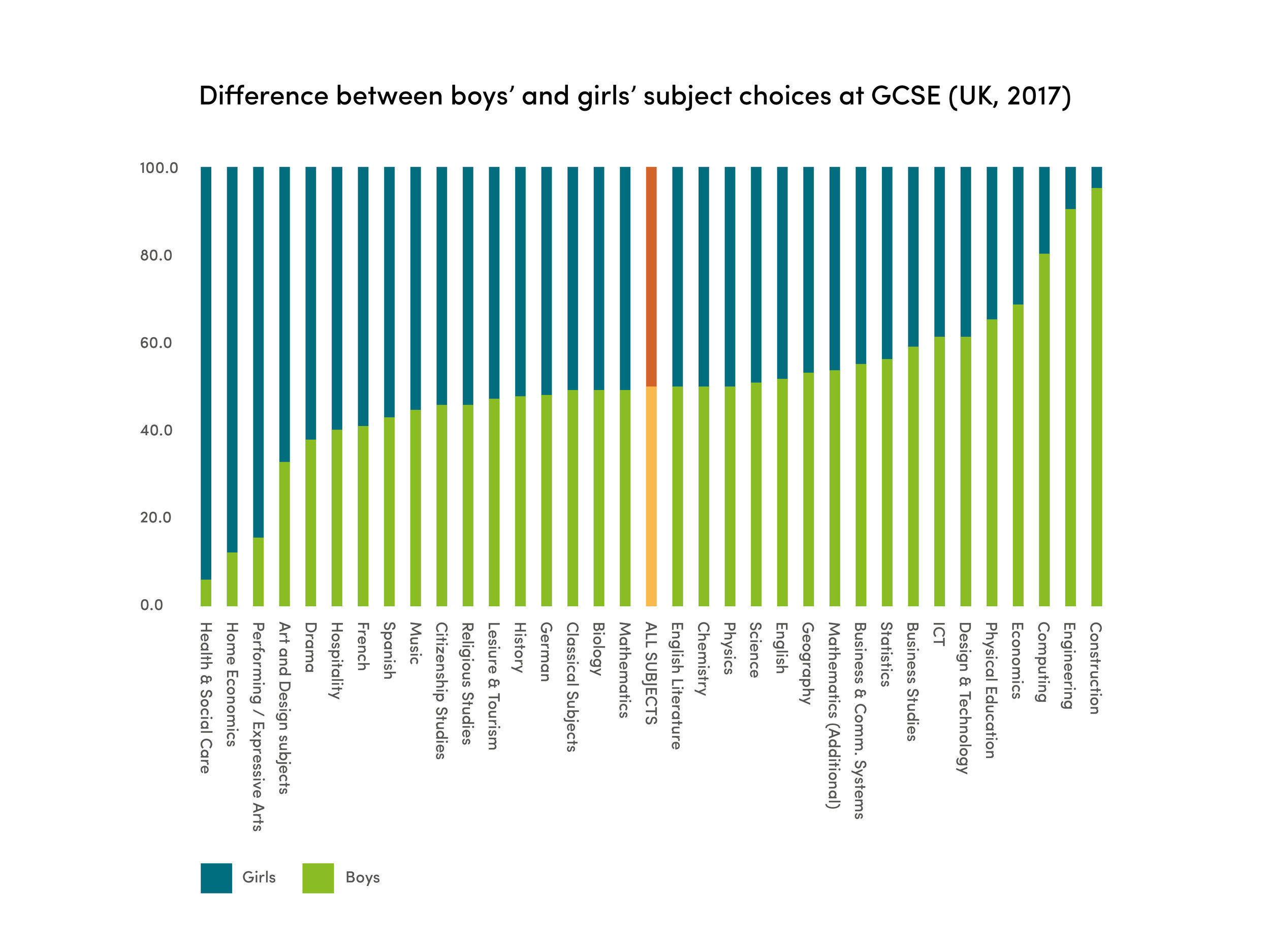

One manifestation of gender imbalance in education is the uneven distribution of subject choice for young people at school. These graphs, using data from the Joint Council of Qualifications, show the subject-divide between boys and girls, and how it grows from GSCE to A-level.

Research has indicated that gender stereotyping and unconscious bias are key factors in limiting the choices of students.

Acceptance of stereotypes can also permit a culture that tolerates sexist bullying, harassment and violence in schools.

“Children whose friendship groups emphasise traditional gender stereotypes – such as boys being tough and girls dressing in a certain way – had lower well-being, and this applied to both boys and girls”

Conducting one-off careers, ‘empowering girls’ or ‘helping boys’ events does not lead to long-lasting change, and good work challenging stereotypes in one area of the school can often be undermined in others. This is why research has indicated that a whole-school approach, and early intervention, is necessary to lead to effective and enduring change.

“Interventions that reduce stereotypical expectations of behaviour and choice are likely to improve boys’ attainment as well as girls’ participation”

Gender stereotypes are not just a problem in the classroom; these stereotypes are internalised and carried through to later life. They affect career aspirations and choices – studies show that children’s ambitions are shaped by gender stereotyping from the age of 7.

“Gender issues are evident from a young age. Girls are less likely than boys to aspire to science careers, even though a higher percentage of girls than boys rate science as their favourite subject. Girls are far more likely to aspire to arts-related and ‘caring’ careers”

What are the effects of stereotypes in the wider world?

These imbalances in subject choice and aspirations obviously have an effect on the workforce. For example, only 3% of early years educators are men and only 12% of the engineering workforce are women.

Early Years Educator data from MITEY UK and Engineering Workforce Data from the WISE campaign

These imbalances also contribute to the gender pay gap – women still tend to dominate lower paid professions such as those in the caring sector.

Stereotypes also continue to affect wellbeing into adulthood. The stereotype of the stoic male prevents men for reaching out for help with their mental health – men accounted for three quarters of deaths by suicide in the UK in 2018.

Even with increasing levels of waged work amongst women, women continue to shoulder the responsibility for unpaid work – on average women do 10 more hours a week than men, as housework continues to be widely deemed women’s work.