Gender equality in early years and primary education: the data

Haleemah Shaffait volunteered from King’s College London to support Gender Action. This blog article is a snapshot of some of the research she has conducted around gender inequity in education, and helpfully highlights national data you can compare your setting to.

Considering gender equality as early as nursery and primary school is essential because that’s when gender stereotypes, and therefore gender inequality, is learned and embedded into behaviour and thought processes. As a result, it is important to consider the language that is used and the stories that are told at the early years level to prevent perpetuating these gender stereotypes. This article intends to provide a general overview of gender equality in the early years and primary so teachers can be made aware of where improvements should be made.

Early Learning Goals

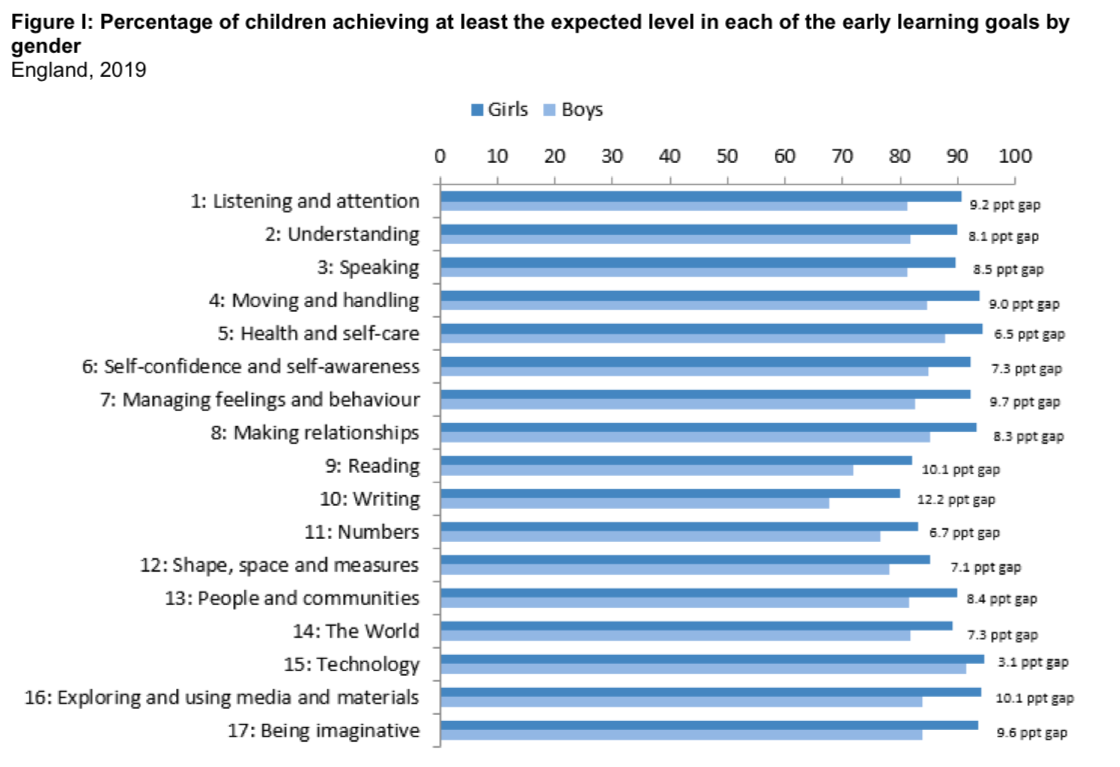

The Department for Education have focused on Early Learning Goals (ELGs), which are certain goals that children should aim to achieve by the end of Reception (Figure 1). 78% of girls are achieving at least the expected level of ELGs, compared to 64% of boys. The smallest gender gap can be seen in technology. The largest gender gap between girls and boys is in writing, reading, and exploring and using media and materials. Practitioners and teachers may wish to consider focusing on these areas.

Figure 1. The percentage of girls and boys achieving at least the expected level of each ELG in England, 2019 (Department for Education)

Key Stage 1 Attainment

Across all Key Stage 1 (KS1) teacher assessment subjects, more girls reached the expected standard than boys. In 2018, 86% of girls and 79% of boys were meeting the standard by the end of Year 1. The smallest gap is in maths, with 77% of girls and 75% of boys meeting the expected standard. However, the largest gap is in writing, with 77% of girls and 63% of boys reaching the expected standard.

Key Stage 2 Attainment

Once again, girls outperform boys at the expected level during Key Stage 2 (KS2) assessments (Table 1). In 2019, 70% of girls met the expected standards in combined reading, writing and maths compared to 60% of boys. However, boys do outperform girls in meeting a higher score/greater depth in their maths test. In 2019, 29% of boys achieved the higher score in maths, compared to 24% of girls. This table outlines where improvements could be made in the performance of boys and girls across KS2.

Table 1. Attainment by gender across all schools in England, 2019 (Department for Education).

Absence Rates

Table 2 is from data collected by the Department for Education. It shows that in general, boys have slightly higher absence rates than girls between the ages of 5 to 11. Children on free school meals (FSM) also have higher absence rates than those not on FSM. Additionally, the difference in absence rates between boys and girls is larger for those on FSM than non-FSM. Therefore, class differences may also play a role in absences.

Table 2. Absence rates by gender, FSM status and age (Department for Education)

Exclusions

Exclusions in primary school are rare. However, boys are more likely to face exclusions than girls. Boys make up 89% of permanent exclusions and 87% of fixed period exclusions, according to the 2019 Timpson Review of School Exclusion. Additionally, the Department for Education has found that in 2017/2018, 35 boys were permanently excluded from Reception, compared to 3 girls. By Year 6, 183 boys were excluded compared to 22 girls. The review hasn’t found clear evidence as to why this is.

This means there is a need to focus on lowering the high exclusion rates for boys in primary schools, as well as considering what may contribute to this.. However, a report by the Children’s Commissioner for England suggests that exclusions at primary school, particularly between Reception and KS1, should not occur at all. The report argues that exclusions at this age are often a result of ineffective behaviour management and school leadership and the behaviour of these children should largely be managed through in-school support, apart from in extreme cases. This means there is a need to focus on meeting the emotional and personal needs of individual children in order to reduce exclusion rates.

Representation

According to the Education Policy Institute, women make up 97% of teachers in pre-primary education in the UK, compared to 44% in the tertiary education sector.

Clearly, there are gender inequalities as to who goes into this profession, as well as who is hired. An over-representation of women in this field may mean there is a lack of male role models for these children. This has wider implications, as highlighted by the Drawing the Future report. It shows that primary school children’s future career aspirations are gendered from the age of 7, with almost nine times the number of girls aspiring to become teachers compared to boys. The girls in primary schools are more interested in ‘caring’ and ‘nurturing’ roles, whereas over four times the number of boys wanted to become engineers compared to girls.

Therefore, there needs to be a focus on both recruiting and retaining men in early years education to help with gender stereotypes.

Overall, it is clear that girls tend to outperform boys from Reception to KS2, which may potentially contribute to the inequalities that exist across secondary schools too. There are also higher absence and exclusion rates for boys compared to girls in primary schools, but it is not confirmed as to why this may be. There is also a lack of male role models in primary school, due to the overrepresentation of female teachers. These are all areas that teachers may wish to consider.